Slow down, take a…

A single piece of advice that I have given more than anything else.

I often find that when I’m advising others, I’m usually giving advice that I need to follow myself.

Over the last two decades managing and mentoring designers, there has been a single piece of advice that I have given more than anything else, and it's quite simple: Slow down.

Easy to say, but it requires an almost superhuman discipline to master.

As I say, this isn’t advice just for the person I’m talking to, but also for myself. Stop, take a moment. Don’t react immediately. Even 10 or 15 seconds can make all the difference in your reaction to a conversation or a problem.

An example from my own life is when I recently noticed that while practicing his guitar, my son was playing the same songs as usual, but very slowly. I asked him why he was doing that. It turns out that his guitar teacher had recommended slow playing to improve his technique. Playing slowly leads to better form, so when he plays at full speed, the notes he produces sound clearer, more precise, and purer.

These are some of the quotes that I find helpful in reminding me to slow down, take a moment, and think.

“The conditions in which wisdom is needed, in other words, are precisely those in which the slow ways of knowing come into their own.”

Hare Brain, Tortoise Mind, Guy Claxton

“Use the first moments in study. You may miss many an opportunity for quick victory this way, but the moments of study are insurance of success. Take your time and be sure.”

Dune, Frank Herbert

When you want to hurry something, that means you no longer care about it and want to get on to other things.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert M. Pirsig

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Questions are the answer

Curiosity > criticism. In the age of AI, success comes from asking the right questions—not knowing all the answers.

If you start a project and immediately jump to a solution, you will only find more questions and problems. On the other hand, if you start a project with the right set of questions, the solution will invariably present itself. Questions reveal ideas that were previously hidden.

Learning to ask questions is about curiosity, rather than criticism, and it’s always a crucial skill to practice., And, in this moment when AI gives us access to all the information in the world, what now becomes most important is being able to find the right questions to ask to get the best results from AI tools. To use these new tools wisely, we’d do well to listen to Neal Postman, who writes,

“Wisdom does not imply having the right answers. It implies only asking the right questions.”

So how do you learn to ask the right question? I would recommend these three books.

Learning to Question

Paulo Freire

"Because, I repeat, knowledge begins with asking questions. And only when we begin with questions, should we go out in search of answers, and not the other way round."

"What does it mean to ask questions?" into an intellectual game, but to experience the force of the question, experience the challenge it offers, experience curiosity, and demonstrate it to the students. The problem which the teacher is really faced with is how in practice progressively to create with the students the habit, the virtue, of asking questions, of being surprised".

Critical Thinking

bell hooks

"The other challenge is to remember not to feel compelled to respond to every question. My training in academic traditions of public speaking taught me to always answer questions even it I did not know the answer; and if I did not know the answer, to act as if I did. What a horrid teaching practice!"

Teaching As a Subversive Activity

Neil Postman

"Once you have learned how to ask questions—relevant and appropriate and substantial questions—you have learned how to learn and no one can keep you from learning whatever you want or need to know"."Prohibit teachers from asking any questions they already know the answers to. This proposal would not only force teachers to perceive learning from the learner’s perspective, it would help them to learn how to ask questions that produce knowledge."

Are questions the key?

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Make your own matrix

What if you can free your mind, you can play inside that perfect virtual simulator, and anything is possible if you can think the impossible.

“This is your last chance. After this, there is no turning back. You take the blue pill, the story ends, and you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill, you stay in Wonderland, and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes. Remember, all I'm offering is the truth, nothing more." - Morpheus, The Matrix

The world is a simulacrum, but if you can free your mind, you can play inside that perfect virtual simulator, and anything is possible if you can think the impossible. This is the brilliant concept behind the movie The Matrix.

But what if I said to you that the new wave of AI LLMs allows you to create a virtual simulation like the Matrix today? If you can imagine what isn’t yet, this simulator will enable you to test out ideas without ever having to leave your desk.

We have all read the stories about AI being the end of design and many other professions. These stories have all focused on the idea that AI can create outputs, screen designs, writing, photography, and apps. But what if we flipped the use of AI? Instead of looking for outputs to create a solution, what if we asked AI to offer inputs and virtual playgrounds to help us understand problems?

For example, if you were designing a new software tool for a healthcare company to help people recover from a medical treatment, you could get an AI to simulate a 56-year-old male who had just had back surgery, and you could step into the matrix (via a Chatgpt prompt) and ask him any questions you thought would be relevant to making your software work for him. There are an estimated 1.2 billion webpages. Somewhere in there is healthcare information that can help you simulate this person fairly accurately.

When you create this person in the matrix, consider imagining and adding details such as demographics, income level, geography, and cultural background. Adding these layers of interconnected information will provide you with better insights into the problem you are trying to solve.

A simple design exercise would be to draw out a series of screens for your new health app. You could ask the 56-year-old man (created from an LLM matrix) what he thought of your screen designs and what the most critical information he would want to see. You could try out different information hierarchies to see which ones made the most sense to him.. Then, you could create another person in the matrix and try out your screen designs with a 26-year-old athlete recovering from an ankle sprain; what would she want to see?

Because your matrix characters would have cultural and geographic context, your simulation could take into consideration a factor like the distance a person has to travel to a local physiotherapy clinic, and your simulation might make clear that the virtual therapy option would be useful for people who have to drive long distances.

Each time you run a simulation in your matrix, you’re able to see the problem you are trying to solve with more clarity. You’ve honed what you’re making, and now, you can take what you’ve learned and try it out with real people who’d need this service or experts who have seen these types of situations.

AI is great at summarizing data; it’s not always a hundred percent correct, but if you do enough matrix simulations with enough types of virtual people and imagine widely and thoroughly, you can figure out where it is going wrong. This is not a replacement for research with real people; it is an additional type of process, a method of inquiry that informs research and enables us to ask better-informed questions.

Build your own matrix today by talking to a taxi driver, a hospital administrator, or a new home buyer. Don’t imagine you’ll get exact answers, but look for the questions unlocked as you run through your matrix virtual simulation. Noticing the gaps and contradictions allows you to ask more insightful questions, which, in my experience, leads to better solutions.

As Morpheus says in the Matrix, "There is a difference between knowing the path and walking the path." AI tools will not magically solve design problems, but they can be used to expand your knowledge and free your mind!

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Luck defines life

Luck plays a much larger role in the success or failure of an idea than anyone would like to admit.

Designers are often focused on a process to control a situation, or they try to cultivate a creative culture to help them solve a problem. Yet, any problem space is filled with unknowns, and luck plays a much larger role in the success or failure of an idea than anyone would like to admit.

The book Fooled by Randomness by Nassim Nicholas Taleb sheds light on the role that luck plays in our lives. It shows that, rather than trying to establish control over everything through science and process, embracing the nature of luck may well be the way to come to terms with the uncertainty of the world we live in today. I thought I’d share a couple of my favorite quotes from the book.

“Remember that nobody accepts randomness in their own success, only their failure.” - Nassim Nicholas Taleb

“What has gone wrong with the development of economics as a science? Answer: There was a bunch of intelligent people who felt compelled to use mathematics just to tell themselves that they were rigorous in their thinking, that theirs was a science. …Indeed the mathematics they dealt with did not work in the real world, possibly because we needed richer classes of processes— and they refused to accept the fact that no mathematics at all was probably better.”- Nassim Nicholas Taleb

The Farmer’s Luck (a Zen story)

A farmer’s horse runs away.

Neighbors say, “Such bad luck.”

He replies, “Maybe.”

The horse returns, bringing wild horses.

Neighbors say, “What good luck!”

He says, “Maybe.”

His son tries to tame a horse, breaks his leg.

“Such bad luck.”

“Maybe.”

Army comes to conscript young men—his son is spared.

“What good luck!”

“Maybe.”

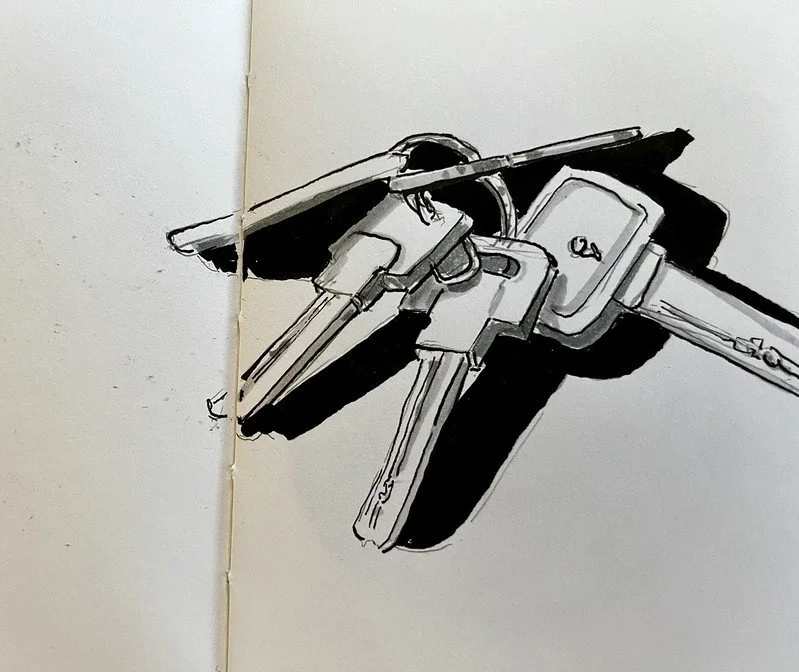

A drawing from my sketchbook

I often make sketch studies of Dorothea Lange photographs. While I am drawing, I often wonder about the individual in the photograph and what role luck has played in their lives.

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Insights are not solutions

Research is often seen as rigorous, while idea creation is seen as a moment of inspiration. Identifying problems and the practice of creating solutions are equally tricky and require radically different skills.

Malcolm Gladwell just released a new book called The Revenge of the Tipping Point. The book is a reflection on his first book, The Tipping Point. In his new book, he admits that he made a mistake.

He jumped to a solution based on research about the broken windows theory, the idea that stopping smaller crimes would prevent larger crimes. With hindsight, Gladwell concluded that he was wrong to jump to that conclusion. (Watch the TED video here: The Tipping Point I Got Wrong )

I am glad he acknowledged this; there is much to be admired in someone who can publicly admit problems with their work. Yet, Gladwell missed another issue with this kind of non-fiction book, which The Tipping Point exemplifies.

The vast majority of nonfiction books are problem books. By this, I mean they allow the reader to access the historical context for an issue/problem space. Climate change, education, crime … the best books among them offer insights, which are hypotheses or concise problem statements of the key issues in that area. But insights are not solutions. Just because you can identify a problem does not mean you are best qualified to create a solution.

As a designer for more than twenty-five years, I cannot tell you the number of times I have heard the phrase "Well, I’m no designer, but I think if you just..." from a well-meaning person who is often an expert in a subject. Creating a solution, or in other words, designing a solution, is not the same skill as identifying a problem. Equally, and from the other direction, a major criticism I have of the design industry is that, in my experience, projects rarely work closely with the people who understand the problem. If they do, the subject matter experts are usually outnumbered by designers, product managers, and executives.

I understand why non-fiction authors often want to (or are pushed to) offer solutions, or what seem to be solutions; readers, media, and publishers ask, How do we fix it? Can you fix it for us?

A different approach to non-fiction is a practice book. It offers practice methods for solving problems, but without much context or clearly defined insights. At their best, they are tools for unlocking ideas.

I remember designing a project for the online division of public television in America. I started by reading "problem books" like Team of Rivals and American Dreamer, which describe the founding of America’s system of government and the New Deal. These books provided insight into the opportunities and problems inherent in public systems and services in America.

When I combined these books with a “practice book” like How Designers Think, which provides a selection of design strategy tools, this practice book allowed me to translate these problem books’ insights through a design “practice” of mental modeling, which enabled me to design a unique and effective solution.

Research is often seen as rigorous, while idea creation is seen as a moment of inspiration. Identifying problems and the practice of creating solutions are equally tricky and require radically different skills.

Combining insights from problem books and practice methods from practice books allows you to unlock something of function and value.

Examples of Practice Books:

Designing Programmes by Karl Gerstner

A technique for producing ideas by James Webb Young

Interaction of Color by Josef Albers

How Designers Think by Bryan Lawson

Examples of great problem books:

The Mismeasure of Man by Stephen Jay Gould

Debt: The First 5,000 Years by David Graeber

American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace by John C. Culver, John Hyde

Bad Samaritans by Ha-Joon Chang

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

People want to play

Work. Does it always have to feel like a grind, or can it feel like play? It turns out your thoughts make it so.

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so”

- Hamlet: Shakespeare.

What if all work felt like play? What if you didn’t worry about results or how people felt about your work? Wouldn’t that feel wonderful?

I want to share a new way of thinking about work—how a change in mindset can make work feel like play.

To explain this shift, it helps to show the elements of this new working style (consistency, focus and play) in contrast to their opposites in the more traditional way of working (ad-hoc, productivity, and results)

Shift one: Moving from ad-hoc to consistency

In addition to completing your regular tasks, start consistently practicing a few specific skills that will help you complete tasks more efficiently. The opposite is to take things as they come on an ad hoc basis, finishing tasks when needed without doing additional work.

Shift two: Moving from productivity to focus

Once you are practicing consistently, focus on a few projects. Creating constraints is vital for focused work. The opposite of this is an emphasis on productivity measured by checking things off a list of tasks in whatever order they come up.

Shift three: Moving from results to play

Once you are consistent in your practice and can focus on a few projects, you build the foundation for play. When you play, you will reorder a sentence to make it funnier or end your meeting agenda on a high note. When you set yourself challenges like this, you grow; when you grow, work becomes easier and more enjoyable. The opposite of play emphasizes results: you finish the task on time, no matter the compromises.

Of course, given the title of this article. You can probably tell which version of work I would like to perform, but as Shakespeare so eloquently stated, there is no good or bad, just different perceptions.

Many successful businesses have been built on the ad hoc, productivity, and results model. The same can be said for the consistency, focus, and play model, e.g., Lego, Patagonia, and Nintendo. It’s less about finding a one-size-fits-all model for working and more about your perception of work.

Does it always have to feel like a grind, or can it feel like play? It turns out your thoughts make it so.

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

D+C Selection: Intelligence in the Flesh

Your whole body is an intelligence ecosystem from the moment you are born.

Humans understand approximately 10-20% of how our brains function. Thinkers have also narrowed our intellect to a single organ in our body, the brain.

In his book, Intelligence in the Flesh, Guy Claxton explores the idea that your brain, far from being the only organ that thinks, is far more like a junction box, connecting intelligence from every part of your body. It’s a fascinating view into intelligence that moves beyond the established logical brain-centered model to understand your whole body as an intelligence ecosystem from the moment you are born.

Highlights from the book

“A cardiologist can give a pretty good account of how the ‘organ of circulation’ works, but after more than a hundred years of scientific psychology we still struggle to give an overall account of this mysterious organ of intelligence.”

“One of the major errors of twentieth-century psychology was to suppose that there are childish ways of knowing which are outgrown, and ought to be transcended, as one grows up.”

“Fundamentally we are not designed for thinking, philosophising or solving cute logic problems against the clock. Reason and debate are themselves tools that evolved to support deeper biological agendas.”

“This being so, we need to rethink the relationship between thoughts and feelings. Feelings are not a nuisance. They are not – as Plato thought, and many still do – wayward and primitive urgings that continually threaten to undermine the fragile structures built by dispassionate reason.”

Prose on logic alone

"The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,

But in ourselves, that we are underlings."

— Act 1, Scene 2 | Julius Caesar |William Shakespeare

A drawing I made called The Watcher

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Your dreams one hour at a time

There is the way you think the world is, and then there is the way the world really is. This is the ongoing battle for all of us: to live in the real world, the world where we get to choose what we want to do, even if it’s only for one hour a day.

Watch the video!

Do you have a special goal? Going on a dream vacation, writing a book, becoming a YouTuber?

How many hours do you have a day to make your dreams come true? For most people I would say it’s about 1 hour a day, which is seven hours a week, or 15 whole days a year.

Now, one hour does not sound like much so let me break down how I came to that number.

Let’s take a typical day for me.

Sleep 8 hours

Cooking/Eating 2 hours

Work 8 hours

Family/ Friends time 2 hours

Admin 1 hour

Travel 1 hours

That is 2 hours left out of 24 hours

That leaves you two hours a day to make it happen. Let’s round down to be realistic and absorb all the tiny, random elements of life I haven’t been able to account for in my breakdown.

When people set a monthly budget for spending, too often they start with how much they earn rather than how much is left after all their fixed costs are accounted for. It turns out that for most regular people, that bit that’s left is not much.

In time budgeting, what’s left over is one hour a day if nothing else goes wrong, and you don’t have to work any extra. It doesn’t seem like much. But constraints are essential for creativity. And you can let go of the guilt of thinking you haven’t spent enough time on your dream project. You only ever really had one hour each day, so you should feel great at the end of the day if you get in a solid hour of work toward your dream.

So how do you use that one hour a day?

Try this exercise and see if it works for you.

Divide your one hour into four fifteen-minute blocks. Now find 4 small objects, 4 dice, 4 marbles, 4 playing cards. Each one of these represents a fifteen-minute block. Place those four objects on the left side of your work desk. Now, during the course of your day, note when you do an activity that is one of your one-hour future goal activities, such as making a drawing, writing to a friend, or planning your weekend break.

Every time you do one of these activities, move one of the small objects on your desk from the left side to the right side of the desk. At the end of the day, see how many objects now live on the right side of your desk. Two, three, four… however many, this is a way of showing that you are using your precious one hour a day in the way that you want rather than just on your fixed tasks for the day. Even if you only move one item from the left of your desk to the right of your desk, it shows progress.

There is the way you think the world is, and then there is the way the world really is. This is the ongoing battle for all of us: to live in the real world, the world where we get to choose what we want to do, even if it’s only for one hour a day.

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Buckets of experience

Experiences fill your experience bucket, otherwise known as your life.

You are born with an experience bucket. It's with you from your very first breath.

From that first moment, you start filling it with experiences—the first sounds you hear, your first touch, the things you see and taste. Each tiny grain of experience fills your experience bucket, otherwise known as your life.

But the one thing that you don't know is that your experience bucket has a hole in the bottom. As a child, you don't really notice the hole. Every day is full of experiences, big and small, and they are constantly filling your bucket, so you don’t hear the sound of the experiences draining away.

But after a while, as you become a teenager, you start to realize that it's harder to keep filling the bucket; you begin to forget things, and you have to start working at filling the bucket. Throughout your childhood, you might also notice that not all experiences are the same. Watching TV or scrolling through social media or webpages are very small grains of experience; they don’t stay with you, they slip right out of your bucket.

Reading books, starting a friendship, writing, and drawing seem to be more substantial pebbles of experience that don't drain away so easily. The more effort you put into something, the longer it seems to hang around, but if you stop practicing, eventually, even these pebbles will disappear down the hole in your experience bucket.

You also start to realize that if your bucket feels full, then life seems better. You might even be able to share some of the pebbles of experience with other people, and in return, they share some of their pebbles to fill your bucket even further.

On the flip side, when you feel like your bucket is getting more and more empty, life seems smaller and less fulfilling. Trying to fill your experience bucket can start to seem harder and harder, so you might just stop trying.

Luckily, some people have help filling their buckets; your parents, friends, and even a like-minded stranger can help. But that is not true of everyone. Sometimes, people empty your bucket.

You can always fill the bucket by practicing a skill, but often, your practice is in a single dimension, and you repeat things you have done in the past. This temporarily fills your bucket with small grains of experience, but that never lasts.

So what do you do? I would say that you need to think of building experiences that are multi-dimensional. In other words, one-dimensional practice leads to very small grains of experience, but multidimensional experiences lead to much larger pebbles (or even rocks) of experience, which, in some cases, will never fall out of the hole in the bottom of your experience bucket.

So, how do you create multi-dimensional experiences?

The first step is, in fact, that one-dimensional experience of practice, but the second step is to create a tool for yourself — a meeting agenda template or a plan for getting fit. Creating your own tool helps build a more robust experience in two dimensions.

Yet, to really make something substantial, it needs to be three-dimensional. You need to share your tools and your experience with others to form a connection to build understanding. This can take the form of making something, books, movies, videos, poems, blog posts, music groups, drawings, anything that allows other people to take part in your experience. These three-dimensional experiences — these bigger pebbles and rocks — don’t so easily slip through the hole in your bucket, and if lots of people start to connect with your three-dimensional experience, then they can form movements and organizations that last the test of time.

Filling your experience bucket is the work of a lifetime, and keeping it full can determine how much you enjoy that life. It's a never-ending process with no endpoint. The more multi-dimensional experiences you create, the less you need to fill your bucket with repetitive experiences like watching TV or scrolling through your Instagram feed, experiences that just slip through the hole in your experience bucket like so many grains of sand.

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

My non-fiction books of 2024

I take my time and embrace the role of randomness.

By asking questions, I learn. Writing down what I have learned helps me explore, and some explorations become pictures. At every step, I take my time and embrace the role of randomness.

Learning to question by Paulo Freire

”I have the impression - and I don't know whether you will agree with me - that today teaching, knowledge, consists in giving answers and not asking questions.”

“Because, I repeat, knowledge begins with asking questions. And only when we begin with questions, should we go out in search of answers, and not the other way round.”

On Writing Well by Willian Zinsser

“I then said that the professional writer must establish a daily schedule and stick to it. I said that writing is a craft, not an art, and that the man who runs away from his craft because he lacks inspiration is fooling himself. He is also going broke.”

“That condition was first revealed with the arrival of the word processor. Two opposite things happened: good writers got better and bad writers got worse. Good writers welcomed the gift of being able to fuss endlessly with their sentences—pruning and revising and reshaping—without the drudgery of retyping. Bad writers became even more verbose because writing was suddenly so easy and their sentences looked so pretty on the screen.”

Thinking in Pictures by Michael Blastland

“How do we do this in practice? One of the best ways is with the most simple, naive questions: 'And is that a big number?' Naive maybe, but powerful. I made half a career from asking that question, and plenty of important people looked silly trying to answer it.8

Here's £10 million for school singing lessons, says a government minister, riding the wave of a popular TV show about choirs. And is that a big number? Context: there are about ten million school kids. What's that when it's mapped? It's £1 each a year, or £30 for a teacher for one class a year, if you're lucky.”

”We tolerate complexity by failing to recognize it. That's the illusion of understanding, say Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach.”

Hare Brain, Tortoise Mind by Guy Claxton

“People’s willingness to engage in delicate explorations on the edge of their thinking could be easily suppressed by an atmosphere of even minimal competition and judgement.”

“Have you noticed how much easier it is for you to tell me about your failures than your successes?”

“This neural model also makes it clear why creativity favours not just a relaxed mind, but also one that is well-but not over-informed.”

“Time spent discovering things for yourself, even though someone could have simply told you the answer or given you the information, may be time well spent if the outcome is greater confidence and competence as an explorer.”

Fooled by Randomness by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

“But there is a more severe aspect of naive empiricism. I can use data to disprove a proposition, never to prove one. I can use history to refute a conjecture, never to affirm it. For instance, the statement

The episode taught me a lot.

Remember that nobody accepts randomness in his own success, only his failure.”

“Science is great, but individual scientists are dangerous. They are human; they are marred by the biases humans have.”

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Suffering is optional

Open yourself to the idea that progress and learning are infinite.

"Pain is inevitable; suffering is optional."

This famous quote from the Dalai Lama might sound slightly harsh, yet I think that what he is saying, in part, is if you set unattainable goals, such as having the perfect job, marriage, children, or education, you will suffer the disappointment of never perfectly attaining those goals.

So, how do you make progress in your life if your unattainable goals can cause suffering?

One popular approach is to set less challenging goals: I want a new smartphone or car. These goals avoid the suffering of disappointment but don’t help you progress because there is nothing more to do once they are attained. As Neil Postman said, "You cannot get better at watching TV."

Set a practice, not a goal.

The first step is to change your mindset, to move away from achievement and finite endpoints, and to open yourself to the idea that progress and learning are infinite. This means that you will be focused on doing new things you are not good at and practicing them daily for 15 minutes. Once you have confidence in one element of whatever skill you are practicing, move on to something else that challenges you. There is no end point; practice is forever.

Many companies have an annual ritual of getting people to set goals at the start of the year. By doing this, they enter what could be a growth opportunity with instead a finite mindset. If your goals are not attained, then everything else you did that year is a failure.

This excellent video clip from basketball star Giannis Antetokounmpoperfectly illustrates the difference between a finite and infinite mindset. "Failures are steps to success."

This year, instead of setting a goal, set a practice. If the skill you want to practice is improving how you present ideas, give yourself 30 minutes each week to give a short presentation to one of your peers. Each person will be different, and that is the challenge. Real practice involves failure, which a goal-based mindset cannot understand.

There are no shortcuts, just practice and consistency. Try to find joy in that. There is no buzz every day, but over time, a quiet confidence that allows you to know that you are capable of most things you set your mind to. Most importantly, you make suffering optional.

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Where do ideas come from?

Ideas go beyond thoughts because they are formulated in a way that allows them to become real.

Ideas are different from thoughts. Thoughts are everywhere and are as common as grains of sand. They are fleeting and often out of context. An idea, on the other hand, is “what exists in the mind as a representation (as of something comprehended) or as a formulation (as of a plan).” - Merriam-Webster definition.

Ideas go beyond thoughts because they are formulated in a way that allows them to become real.

Here are some inspirations for ideas to try, read, and think about.

In A Technique for Producing Ideas by James Webb Young, the author outlines his method for the production of ideas, underscoring that they don’t just arrive, but must be made.

“As I said before, what I am now about to contend is that in the production of ideas the mind follows a method which is just as definite as the method by which, say, Fords are produced.”

There are many ways to have ideas, Creators on Creating is a great book that outlines how many of the most creative people develop their ideas.

One practical way of creating ideas is the 9-box method. Get a piece of paper, draw a three-by-three grid of boxes, Write your problem statement at the top of the page, and then fill each box with an idea that might solve the problem you are trying to tackle. This method allows for a breadth of thinking and comparison between ideas.

One of the best apps I have found for gathering ideas is Readwise. It allows you to highlight quotes from Kindle or other online readers and organize those ideas to act as a springboard for your own ideas.

Musician Brian Eno is famous for being an ideas person. He believes in a concept called Scenius, which means that ideas are not just generated by individuals but by groups of people all thinking independently and then coming together to make an idea.

I will leave you with this thought about ideas from the excellent book Hare Brain Tortoise Mind.

“One of the strongest forces that prevents the discovery of these new avenues may be the habit of thinking fast: of taking your first intuitive assessment of the situation for granted, and not bothering to stop and check.”

A question…

How do you come up with ideas? Please take a moment to share your thoughts on what works for you.

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Listening is the first step

Listening and curiosity are two vital skills for creativity to thrive.

“Today, in conversation, I try to constantly remind myself: only react, only intervene, when invited or when it will obviously be welcome. This takes practice, possibly endless practice.” - Carl Rogers

This quote inspired me to create a design exercise with my team. How can you practice active listening? What is active listening?

For me, it’s the ability to let go of your thoughts and feelings and formulate questions about what you hear. In other words, to be actively curious. This means going from a passive state of absorbing knowledge to an active state of thinking about what you heard and formulating questions based on that new knowledge—a practice driven not by self-interest but by curiosity.

This unlocks a whole new world where you can move beyond your thoughts into someone else’s ideas.

The exercise I devised for my team was to watch three videos and, after each video, spend 5 minutes writing down the questions that arose for each of them from watching each video.

Here are the three videos I used.

Andy Goldsworthy on the work of art

Lewis Hamilton on teamwork

Brian Eno on culture and creativity

After 30 minutes of this exercise, we generated over 60 questions as a group. This started a wide range of conversations among the team. For me, this is a victory for listening and curiosity, two vital skills for creativity to thrive.

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Teaching critique

Not only do we need to offer criticism, but we need to provide tools to help people critique their own work.

A critique session is often a moment to teach. But what does it mean to teach?

I found this quote recently, which resonated.

“It means that your students can look at the work and make similar decisions without you being there.” - Dr Samuel Holtzman

Not only do we need to offer criticism, but we need to provide tools to help people critique their own work.

To that end, I wrote this article, “Design proofreading.” It offers a tool to help you understand how I critique UX design work. I hope it proves helpful to you as you work through your next project. There are no magic solutions to making great designs, no secret methods other than spending time understanding the problem, trying out a variety of ideas to see what fits, and then critiquing those ideas.

Every critique teaches you something, and the trick is to be open, to listen, to let go of your preconceived ideas, and to be ready to move on to the next idea.

If you liked this article, please share it with just one other person. Word of mouth is a great way to help Design + Culture grow. Thanks

Fear is the motivation-killer

Find your people on your “team for life.” They will open endless doors of insight, discovery, and motivation.

“I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.” - Frank Herbert, Dune.

In today’s culture, we are constantly afraid. What will be the next disaster for yourself or your community? Cybercrime, subway muggings, bridge collapses, wars, and global pandemics. 24-hour news coverage of all these fearful events is constant. Ẽven observing them from the edges, it would be reasonable to feel fear. I certainly do.

The problem is that this fear robs us of our agency. If you allow it to overwhelm your mind, you become passive, waiting for the next disaster rather than living your life. So, how do you fight this? How do you find the motivation? How do you face your fear and permit it to pass over and through you?

One approach is to change the rules of the game. Right now, there are more sources of news and information than ever before in human history. In previous eras, people didn't know what they should be afraid of because they didn't know about events on the other side of the city, let alone the globe. Now, you can access everything immediately through your magic rectangle, always within arm’s reach.

But what if you changed the rules of the game? What if you went from being a passive information sponge to diving deeper into the ideas that speak to you? Rather than feeling fear, you pick the type of information and make it work for you instead of against you, providing you with a source of courage and motivation.

Find your people

Have you ever felt deeply connected with an idea you have read, watched, or listened to? An author or artist that you could not stop thinking about? What if we thought of that person as part of your “team for life” — a group of people who would help inspire and motivate you for the rest of your life?

It's fine to have a small team to start, and your team might change over your lifetime as you discover new people and ideas and as you yourself change. You might say, but I’ve read that book and listened to that music a thousand times. How do I keep getting motivation from that one person? This is where the internet in that magic rectangle can instead come to the rescue. We live in a time when a large part of human creation is accessible (or at least a large part of human knowledge). If you like a particular person, chances are so do a lot of other people. Those other people might have written a book, conducted an interview, or made a movie about your inspirational person. Luckily for you, all of that stuff is now only one click away. Apple podcasts or YouTube are excellent starting points.

Everyone’s “team for life” is unique to them. So it’s easy to be self-motivated to find this information because these are ideas and people you have picked. The deeper you dive into the people who get you, the more you learn. Your “team for life” is always there for you, showing you new places to explore, books to read, and things to listen to. This is also an excellent antidote to information overload, a filter on the internet.

You could pick from some of the usual suspects: Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, Steven Spielberg, or the Beatles. But the people you pick don’t have to be famous; they just have to get you. Appeal to your particular way of thinking, the thing that motivates you. For example, I like Shakespeare, Neil Postman, Adam Curtis, and Georges Simenon. Now, that’s just me, but when I watch a Shakespeare scene or listen to an interview with Neil Postman, it motivates me to keep exploring. That motivation turns into things like starting to write this article.

Pick your team for life

Take 10 minutes, sit down, and write a list of people that you really enjoy reading, listening to, or watching. Don't worry if it’s hard at first or if you pick the wrong people. Your team is going to change and evolve as you do, and that's a wonderful thing. Once you have two or three people jotted down, open up a podcast app or YouTube, visit your local library, and look for anything about that person: interviews, music, movies, books, articles, anything that allows you to explore their ideas further, and make a playlist. The next time you’re bored or lack motivation, just pick something off your "team for life" list and enjoy.

Introduce other people to your team and share their ideas with your work colleagues or with your friends. It might fall flat, or it might be the opportunity for someone to find a new member of their own “team for life.” Find your people on your “team for life,” and they will open endless doors of insight, discovery, and motivation. This will allow the fear to pass over and through you, and what will remain is the most motivated version of you.

Look outside yourself

“But the greatest benefit is to be derived from conversation, because it creeps by degrees into the soul.” - Seneca

Have a problem at work? Try a mindfulness app. Have a family conflict? Feeling sad? You guessed it, try a mindfulness app.

What if instead of using an app to look inward for solutions, we looked outward?

If you feel your attention is scattered, you can practice meditation, breathe, and build your focus skills.

You can also make a coffee date with a friend once a week and sit and listen. Resist the temptation to offer quick fixes or anecdotes from your past experiences; just listen. I would argue that this would build your focusing skills just as much as any mindfulness app might. Sitting and listening also provide a new perspective on your own issues.

Modern culture has gone from a collective sense that we are interconnected to an almost robotic individualism, which is leading to record levels of anxiety, loneliness, and worse. The BBC writes, “suicide is now the second-leading cause of death among Americans under the age of 35, according to the Centers for Disease Control, America's health protection agency.”

Meditation and mindfulness clearly have a place but even monks talk to each other, they share ideas, problems, and chores.

If you want to get fit, get a personal coach. If you want to improve your mental health, get a therapist; if you want to learn a language, take a course with a teacher and class full of fellow learners.

While you can improve all these things by yourself with a smartphone, doing them with other people helps not only with learning a new skill, it also helps with the more intangible social learning which neither a device nor your inner voice can provide alone.

I am not advocating for returning to offices five days a week or only getting fit at a gym, but there needs to be some counterbalance to the relentless message that everyone fixes themselves alone, which seems to erode our culture one person at a time.

Even my favorite stoic, famously inward-looking, wrote,

“But the greatest benefit is to be derived from conversation, because it creeps by degrees into the soul.” - Seneca

The power of archives

I love archives; they connect with our past and help us understand our present and future.

Ramesses II died in 1213 BC. Venerated, he lived 90 years, a ripe old age by modern standards. But when you realize that the average Egyptian at the time died by the age of 25, that would be the equivalent of a person today who lived to 400. You can see why he seemed like a deity.

I found this cultural gem in a story about the British Museum's giant statue of King Ramesses II in an archive called A History of the World in 100 Objects, created by the British Museum and the BBC. It's a 100-part podcast series that views the history of the world through the lens of objects from the British Museum.

This kind of archive is not just a collection of items or stories; it is a carefully curated collection with a function, purpose, and vision.

I love archives; they connect with our past and help us understand our present and future. These invaluable resources are often collected and curated by driven individuals to ensure we maintain this connection with the past and its rich source of culture and knowledge.

Here are some archives I have found and created that have captured my imagination. Please check them out and share any archives you have found with me. I would love to see, hear, and watch them.

History of the World in 100 Objects

This fantastic collaboration between the BBC and the British Museum tells the story of civilization through objects curated from the British Museum's catalog.

A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

This one-person odyssey of an archive tells the story of rock and roll through 500 songs, providing a rich cultural history.

The Studs Turkel Archive

A brilliant author in his own right, Studs Turkel had a radio show for 45 years, and the archive of his interviews allows you to listen to fascinating regular people and some of the most influential people in the culture of the twentieth century: the juxtaposition makes this collection unique.

Over the years, in collaboration with various organizations, we at Buscada have created archives covering multiple topics and ideas. These are some of my favorites:

This Triangle Fire Open Archive

Following this significant tragedy for working people over a hundred years ago, the archive collects political, cultural, and personal objects and stories that show how much this event has shaped our modern world.

Working with People

This video archive examines words like collaboration, community, power, and representation and allows individuals to express their diverse perspectives on the meanings of these words. They are creating a space for dialogue and nuance around some of the most critical issues of our time.

Family List

This is our project to curate activities for kids to try, make, and play. It focuses on diverse books, play activities, and cultural ideas to help kids and adults understand the world around them through play.

Investigating design

Adopt a detective's perspective to unravel the complexities of your design challenge

A software product designer is often given a problem like this:

“People cannot figure out how to share a document using our current software experience.”

It’s natural for that designer to want to talk to end consumers of the software and ask them what the issues are with the software experience. When they do, they often hear responses like, "It’s just not clear," or "I don't even know where the button is,” or "This is not how it works on Microsoft Word." These conversations might offer valuable insight, but they don't really help a designer understand the whole problem; the feedback is about specific parts of the problem but doesn’t form a complete picture of the experience.

But what if this was a mystery?

What if there was a crime, a murder! it happened in the middle of the day, and there were several witnesses, but none of them actually saw the dirty deed.

Interview the witnesses

You would interview the witnesses - just like in our software design problem when the designer talked to the users. But where would you be if you just stopped there without examining the crime scene or forensics?

The crime scene

At the murder scene, we’d investigate the details of the space. Too often, in software, we overlook those spaces where it all happens: the software screens, the buttons, menus, fields, and workflows. There is much to be learned from those old screens, like from a crime scene.

Forensics

Where did people click? Could they understand the labels? Was it clear that this item could be shared? What is all the functionality that's available? In other words, let’s establish the facts so we can see the whole problem.

Put the pieces together...

Once you’ve interviewed the witnesses, investigated the crime scene, and have all the facts in place, you can recreate the sequence of events that led to the crime (the user experience). You can see what is happening and why it's going wrong. You can take all those eyewitness statements (user interviews), put them in context, and make sense of them.

Once you can see what happened in a design, unlike a crime, you can change what will happen. As a designer, you can change the sequence of events and alter the facts to make the outcome something that engages your users and helps them get things done. In other words, you can create a design that is no longer a crime.

Reactive vs Proactive work

Balance is essential. You don’t need to control everything, but you do want control over some aspects of what you do. Doing proactive work can help you achieve this balance.

A recent official report on Fostering Innovation by the British Psychological Society, having surveyed all the relevant research, concludes that: ‘Individuals are more likely to innovate where they have sufficient autonomy and control over their work to be able to try out new and improved ways of doing things’ and where ‘team members participate in the setting of objectives’.

Hare Brain, Tortoise Mind - Guy Claxton

Office workers now have more autonomy than ever, and it’s clear that people feel that autonomy is important to them—yet understanding how to use this newfound freedom is often challenging. Autonomy needs a new mindset.

To take advantage of your newfound freedom, you need to consider the balance of reactive versus proactive work that you do.

How do you know if you are doing reactive work?

Are you executing on work set out in the project plan and primarily responding to other people’s requests?

How do you know if you are doing proactive work?

Are you planning how you’ll approach your work?

Here’s an example of choosing one of these two ways to work in response to the same scenario. Your boss briefs you on a new project. You can:

A: Wait for your boss’s project plan and for someone else to schedule a kickoff meeting.

B: Make your own project plan, research the subject matter, and schedule meetings with end users of this project.

While plan B sounds like a lot more work, it has the benefit of being proactive, putting your needs out in the world, and communicating what you want to achieve with the project. Even if you don’t get everything you want, you might get more than you imagine. In addition, you will be much more motivated to do a task you set yourself rather than being told what to do.

Balance is essential. You don’t need to control everything, but you do want control over some aspects of what you do. Doing proactive work can help you achieve this balance.

No matter what your level in your organization is, proactive work can have an impact. If you are an intern, it’s a way to ensure you get a chance to do more exciting work. If you are mid-level in your career, it lets you set the tone for a project, and if you are a leader, it enables you to control your most precious asset, your time.

My books of 2023

Change is the one constant in life; it’s also the key theme in some of my favorite books from this year.

Change is the one constant in life; it’s also the key theme in some of my favorite books from this year.

Maybe you are like spy George Smiley, looking forward to retirement before having your world turned upside down, or maybe you are like John Cleese, discovering the power of your subconscious mind and its ability to change how you think. The artist Wayne Thiebaud recalls his ability to change between being an acclaimed artist and a teacher. Peter Ackroyd details the amazing roller coaster ride of change that is British history.

Adapting and changing is a crucial ability in life, and W. Timothy Gallwey’s great book The Inner Game of Work helps you find ways to focus on the change you want.

I hope you find a book here to take into the new year that can help you focus on the change you want in 2024!

The Inner Game of Work

W. Timothy Gallwey

The spy who came in from the cold

John Le Carre

Creativity: A Short and Cheerful Guide

John Cleese

Foundation: The History of England from Its Earliest Beginnings to the Tudors

Peter Ackroyd

Wayne Thiebaud: Draftsman

Isabelle Dervaux